Just one quick mistake will result in an injury to your ankle. An ankle sprain is a common musculoskeletal injury. The injury occurs when the ligament in the ankle is stretched. Some people attempt to fix ankle injuries without undergoing treatment. Often ankle sprains cause more severe pains and bruises than just minor pain.

Most sprained ankles have excellent results despite their severity. After the proper treatment, the majority of people can resume normal work, sport, etc after some duration. Importantly, success in rehabilitation is conditioned on the patient’s participation in rehabilitation exercise. Incomplete rehabilitation is the leading cause of chronic ankle sprains. If someone stops doing strengthening exercises, their injured ankle muscles will become thinner, causing them to suffer ankle sprains as time passes.

An ankle sprain is a common sports injury among athletes in all sports and often goes untreated. Many people have experienced a sprained ankle, but unfortunately, most do not realize that the lack of appropriate management can potentially lead to recurrent ankle sprains and chronic issues/dysfunction.

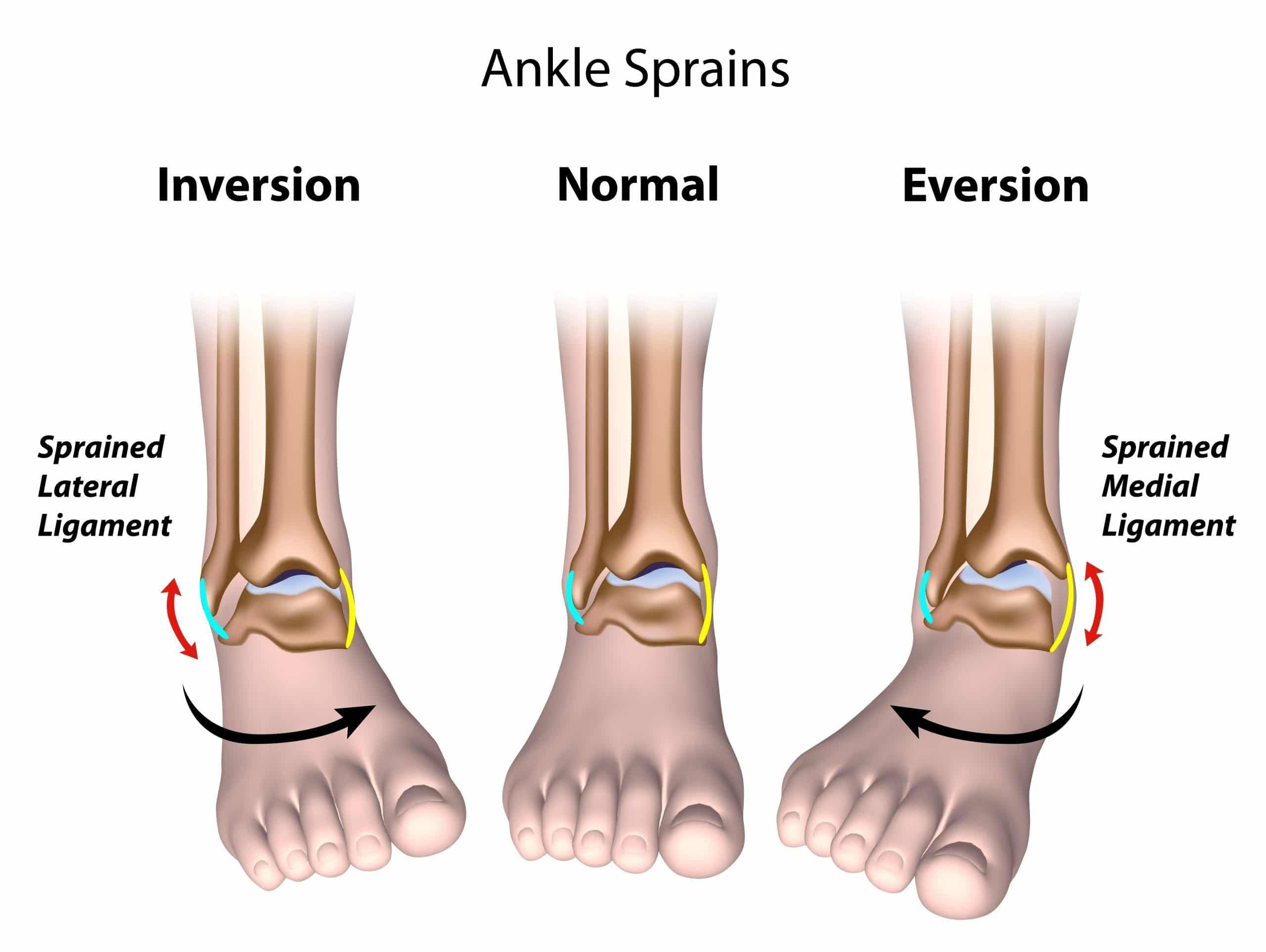

The “common” ankle sprain occurs secondary to an inversion injury in which the foot ‘rolls or turns in’.

The severity of the injury and which ankle ligaments are involved varies based on the force and positioning of the foot and ankle at the time of the injury – ATFL involvement is most common.

The severity of the ligamentous injury is defined as Grade I stretching of the ligament(s) with small tears, Grade II significant partial tear(s), and Grade III complete tear of the ligament(s). Additionally, ankle musculature can be overstretched specifically the peroneal muscles, which also run on the outside of the ankle and help with actively stabilizing the ankle.

Pain and swelling are usually focal to the lateral (outside) aspect of the ankle and foot. Severe pain is often accompanied by tenderness, warmth, swelling, weakness, bruising, and limited range of motion (ROM) immediately following the injury.

As the pain and swelling resolve, patients often complain of a “pop” or “snap” when the injury occurred as well as instability or “giving way” of the ankle with weight-bearing activities.

The Ottawa Ankle Rules have been developed to help clinicians determine if images (x-rays) are needed to rule out a broken bone after an acute ankle injury. During a physical exam, the ankle is thoroughly assessed to determine the severity of the ankle sprain and the proper treatment which typical is a nonsurgical treatment.

There are many different treatments for ankle sprains, depending on the severity of the injury. The most common you hear about is R.I.C.E.

The goal of RICE therapy is to minimize swelling and pain.

Rest: Avoid activities that put stress on your ankle. You may need to use crutches to keep weight off your ankle.

Ice: Apply ice to your ankle for 20 minutes at a time, several times a day. Do not put ice directly on your skin. Wrap it in a towel first.

Compression: Use an elastic bandage or compression sock to help reduce swelling. Do not wrap it too tightly.

Elevation: Keep your ankle above the level of your heart, on a pillow or recliner, to help reduce swelling.

While many still encourage R.I.C.E., research has led clinicians to believe that this may actually do more harm than good in the long run. Prolonged immobilization has been shown to lead to increased stiffness and weakness as well as atrophy (shrinking) of the muscles. Additionally, there is evidence to support that ice delays healing by decreasing cellular metabolism.

MOTUS physical therapy helps people with ankle sprains recover more quickly than they would if untreated or the ‘traditional R.I.C.E’ method. The time it takes to heal an ankle sprain varies greatly, but a return to sport can often be achieved in 2 to 8 weeks at MOTUS. Your physical therapist will work with you to design a specific treatment program that meets your needs and goals.

Modification of daily and physical activity is often needed to allow healing to begin.

For acute ankle sprains, recent research has shown that talocrural distraction mobilization (grade V) performed by a skilled physical therapist both diminishes pain and increases the range of motion. Early ankle joint mobilizations and ROM exercises aimed at dorsiflexion recovery are essential in combating trouble walking, long-term pain, future sprains, and ankle instability.

Once ROM is achieved and swelling and pain are controlled, the focus of therapy then shifts to restoring the patient’s strength, proprioception (joint position sense), and normal ankle biomechanics. Strengthening of the small muscles of the foot and ankle is needed to increase the dynamic stability of the ankle.

As the patient achieves full weight-bearing without pain, proprioceptive training is initiated for the recovery of balance and postural control. A common progression when performing balance exercise is to move from bilateral (double leg) stance to unilateral (single leg) stance, eyes open to eyes closed, firm surface to unstable or uneven surface, and uneven or moving surface.

The advanced-phase rehabilitation activities should focus on regaining normal function. Functional strengthening exercises may include plyometrics, running, jumping, and agility activities that will prepare the athlete to return to their respective sport.

The decision to return to play following an ankle injury is a multifactorial process. Functional testing may be utilized to gauge an athlete’s progression through the rehabilitation process. Testing includes balance, proprioception, strength, range of motion, and agility assessments to determine physical readiness to return to sport safely.

The most common long-term complication following an ankle sprain is the development of chronic ankle instability (CAI). When ankle ligaments are overstretched or torn, they do not completely heal to their original length or strength. This can lead to a feeling of giving way or instability in the ankle which predisposes an individual to further sprains. It is characterized by a feeling of “giving-way” or instability in the ankle, which can occur with activities such as walking or running.

CAI is a progressive condition, meaning it will continue to worsen without proper treatment. If left untreated, ankle instability can lead to severe pain and further injury, including breaks or fractures in the ankle bones.

- Bachmann, L.M., et al., Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ, 2003. 326(7386): p. 417.

- Hultman, K., A. Fältström, and U. Öberg, The effect of early physiotherapy after an acute ankle sprain. Advances in Physiotherapy, 2010. 12(2): p. 65-73.

- Loudon, J.K., M.P. Reiman, and J. Sylvain, The efficacy of manual joint mobilisation/manipulation in treatment of lateral ankle sprains: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med, 2014. 48(5): p. 365-370.

- Denegar, C.R., J. Hertel, and J. Fonseca, The Effect of Lateral Ankle Sprain on Dorsiflexion Range of Motion, Posterior Talar Glide, and Joint Laxity. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2002. 32(4): p. 166-173.

- van Ochten, J.M., et al., Chronic complaints after ankle sprains: a systematic review on effectiveness of treatments. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 2014. 44(11): p. 862-C23.

- Mattacola, C.G. and M.K. Dwyer, Rehabilitation of the ankle after acute sprain or chronic instability. Journal of athletic training, 2002. 37(4): p. 413.

- Clanton, T.O., et al., Return to Play in Athletes Following Ankle Injuries. Sports Health, 2012. 4(6): p. 471-4.